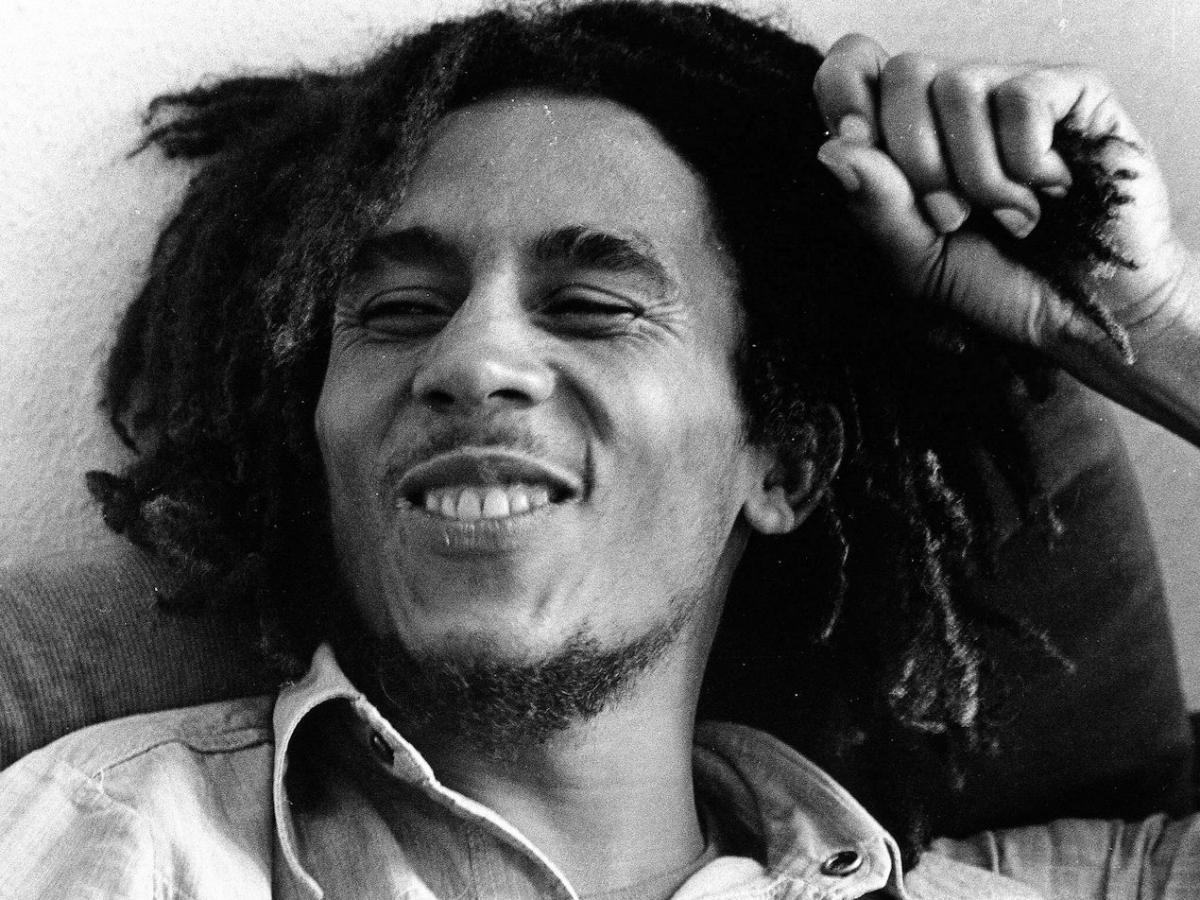

If you're a fan of music books, you almost certainly know Richie Unterberger's name, and, in fact, there's a good chance you might have read one of his books. Unterberger has authored books on many diverse artists and bands, including The Who, The Velvet Underground, Fleetwood Mac, The Beatles, and The Byrds, among others. His latest book is Bob Marley and The Wailers: The Ultimate Illustrated History. We spoke with him and asked "Five Questions" about this beautiful book. Here's what Richie had to say.

Given the lack of record-keeping in Jamaica in the ’60s and ’70s, and the aging of many of Marley’s contemporaries, how difficult was this book to research, and what methods did you rely on?

Given the lack of record-keeping in Jamaica in the ’60s and ’70s, and the aging of many of Marley’s contemporaries, how difficult was this book to research, and what methods did you rely on?

My role in this book was to provide the text for a heavily illustrated coffee table volume on a major artist’s life and career, in line with other Voyageur Press books in this series (such as the one I did for Fleetwood Mac). So the 50,000 words or so I wrote were an overview, hopefully providing both an introduction for the general reader and some more in-depth information and critical description for those who are familiar to varying extents with Marley’s work. It’s not as long as some other Marley volumes, but I do think this tells the essential story of Marley and the Wailers in a way that’s more succinct, direct, and music-focused than other books.

Bearing this in mind, my research involved going through a great deal of material that’s been written about Marley, as well as documentaries and audio/film interviews. I funneled the most essential details into a story that I hope is both readable and entertaining.

This isn’t as easy an enterprise with Marley and the Wailers as it is with many artists whose lives are more accurately documented. There are a lot of vague and contradictory accounts of what happened when, particularly for the first decade or so of the Wailers’ career, prior to when they signed with Island Records and put out their first album with good international distribution, 1973’s Catch A Fire. I did my best to objectively balance these accounts by noting different views and reports about the events and the Wailers’ motivations, and making educated guesses as to what and why things happened as they did.

Fortunately there were quite a few articles on, and good number of interviews with, the Wailers from 1973 onward. I consulted dozens of these, some of them quite obscure, and sometimes quoted from them (with specific attribution) in the book.

What surprised you most that you didn’t know about Marley in researching the book?

I did know a lot about Marley before doing my research, and most of the surprises concerned the extent of murkiness surrounding specific details about his early career, rather than events or records I wasn’t aware of at all. That noted, writing the early sections in particular did bring home to me how much still remains to be ascertained about his pre-1973 life, and how much likely never will be known for sure.

After digesting all of this, I felt that his role in the Wailers, and the Wailers’ progression to international stardom as a whole, was more fluid, erratic, and impermanent than I’d realized. A good number of the early Wailers records are missing one of the three principal figures (Marley, Peter Tosh, or Bunny Wailer) when one or the other was out of Jamaica, in jail, or just not around. A good number of them have other singers whose contributions aren’t too well known, including Bob’s wife Rita. Marley at various points went on extended overseas trips without the Wailers to the US, Sweden, and the UK, leading one to suspect that he might have been weighing a solo career without Peter and Bunny if that led to an international breakthrough. There was some good fortune involved in the Wailers actually getting a deal with Island Records before they might have broken up or Bob gone on his own, though those three core Wailers actually wouldn’t work together at Island for too long before going their separate ways.

As just one surprising thing I did not know, the Wailers actually did some shows – poorly documented, as so much of their early career unfortunately is – in the Eastern part of the US in early 1972, nearly a year before they approached Island Records. That indicates that maybe they hoped somehow to be able to make it in the States, although they probably couldn’t have done that as well without the backing of Island Records chief Chris Blackwell. There were some other mysteries about the early Wailers no one’s really gotten to the bottom of, and in addition to noting them in my book, I discuss some on my blog in a three-part series here.

The Wailers are one of the great backing bands in history. What did you learn about them that you didn’t know?

As this question refers to the Wailers as a backing band, I’m assuming it’s asking about the period from the mid-1970s onward, after Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer left, and the group continued billed as Bob Marley & the Wailers. Again I knew the basics of their story well, eliminating major surprises. But putting the whole story in focus set in relief how Marley did move toward more of a rock sound in the second half of the 1970s. In particular, he did so by using a couple of American guitarists, Al Anderson and Donald Kinsey, in some Wailers lineups. Before that, the Wailers (abetted by Chris Blackwell) put some overdubs on Catch A Fire by rock guitarist Wayne Perkins. I don’t see this as a sellout, but as a successful attempt to broaden reggae’s musical scope and its audience.

I remembered Kinsey being interviewed for a story almost thirty years ago for a small magazine I worked for at the time, Option. From that article, here’s an example of a quote I excavated as part of my research, in this instance illuminating how Kinsey changed the Wailers sound: “When I first got with those guys, the reviews that were coming out! ‘Donald Kinsey bringing blues to reggae.’ Some would write about it as if it was a positive thing, and others would write about it as if it was a negative thing. But I knew it was a positive thing and Bob and Peter knew it was a positive thing, too. It helped give the music a different type of flavor. The guitar players in Jamaica weren’t into string bendings and the blues type of style. They were more into just a rhythm type of thing.”

What was Marley’s greatest musical impact?

From the start of the Wailers’ career – even when they were making ska records in the mid-1960s, whose themes were often devoted to romantic love and having fun – Marley and the other Wailers were possibly the best songwriters in reggae (or what would become reggae, back at their inception). Even on their ska sides, they sometimes referred to tough conditions in the ghetto on songs like “Rude Boy.” In the late 1960s and early 1970s, they increasingly brought social consciousness and spirituality (sometimes informed by the Rasta faith) into their songs. They had other kinds of songs as well, and they weren’t the only reggae artists to do this. But they were the artists most responsible for doing so.

After Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer left, Marley’s biggest impact was as a popularizer of reggae throughout the world. As previously mentioned, he sometimes did so by bringing elements of rock into his sound. Had he lived, he might have gone in other directions from a reggae base, as he famously did on “Redemption Song,” which is almost folk in its arrangement and delivery.

Also, with the Wailers he was the artist most responsible for making strong reggae albums that were standalone statements, in a style that before the 1970s was almost exclusively singles-oriented. They were doing this in Jamaica in the early 1970s even before signing with Island Records, at which point they become even more album-oriented, especially with more time and funds for recording in the studio.

I should note I don’t think you can assess Marley’s musical impact without noting how vital the contributions of Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer were over their first decade. The other two guys weren’t just singers in a backup band; they were both strong songwriters and lead singers, and even on the songs they didn’t write, were crucial as harmonizing vocalists (and sometimes instrumentalists). If they’d continued together, it’s possible you could have had more diverse Wailers albums with three strong singer-songwriters, a la white rock groups such as the Beatles, though that didn’t happen for many reasons.

How about socially and culturally? His message of unity and love seems to resonate more than ever now.

I think Marley’s greatest sociocultural impact was as a musical spokesperson of sorts for the underprivileged, and for many people of color, throughout the globe. As I said not all the Wailers songs were socially oriented, but many of the ones that were protested the suppression of the poor and minorities. Many did so not just through anger, but through giving people a sense of empowerment, as on one of their most famous such songs, “Get Up, Stand Up.” The songs without a specific social dimension served their purpose as well, simply by creating positive vibrations that were easy to groove to and made people feel good about themselves, whether “Stir It Up” or “Jammin’.”

In these times more than some others, unity, peace, and love seem hard to achieve, and not values cherished by some of the world’s most powerful figures. Marley’s messages along these lines can be lyrically basic, but they are powerful because their musical strength and accessibility can be easily appreciated and understood throughout the globe, even in many countries where English is not the primary language. He sometimes backed up his music with action, most famously at the 1978 Smile Jamaica concert in Kingston where he somehow got rival political leaders Michael Manley and Edward Seaga to clasp hands onstage. That didn’t mean that suddenly things were peaceful in Jamaica, but it set an example that people with seemingly irreconcilable views could at least set their daggers aside, if not agree on everything.

I also think he was an inspiration to many residents of the Third World in particular, simply because he overcame seemingly impossible odds to rise from poverty in Jamaica to international stardom and reverence as a cultural figure. Jamaica is not as bad off as many Third World nations, but there’s a lot of poverty and social instability in the country, more so in Marley’s time than ours. His successful delivery of a new kind of music, from a small country outside the North American/European continents that dominate popular culture, to the world stage made others throughout the Third World feel that they too could have their music heard and appreciated everywhere.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

#bookreviews #musicbookreviews #richieunterberger #bobmarley #bobmarleyandthewailers #reggae #ska #petertosh #bunnywailer #chrisblackwell #islandrecords #voyageurbooks

- Admin's blog

- Log in or register to post comments